What is COPD?

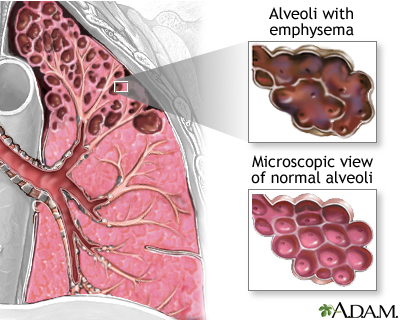

COPD or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is one of the most common lung diseases related to smoking. It is otherwise known by patients as “smoker’s cough” or “emphysema.” In truth, it is a spectrum of disease that includes inflammation and irritation of the airways with excess mucus production (bronchitis or bronchiectasis) , spasm and constriction of the airways with chest tightness and cough (asthma) , and destruction of the airways with shortness of breath (emphysema) and the need for supplemental oxygen.

Why am I short of breath now if I stopped smoking years ago?

Many of my patients think that because they quit smoking years ago, it seems strange that now, years later and seemingly “out of the blue” they have the symptoms of COPD. The truth is that the airway damage was present years ago when they were smoking, but they had so much healthy lung remaining, that it was well-compensated for and they never noticed it. Over time, the body wears out, otherwise known as aging. Lung function also steadily diminishes in a predictable and measurable fashion. As the healthy lung becomes aged, and less able to compensate, the symptoms of the damaged lung become move evident and noticeable.

How does the lung damage occur?

Just like the rest of the body, the lung has two possible reactions to damage and injury. It can heal without a trace of damage (as seen following a brief respiratory infection) or it can scar. Replacing damaged tissue with normal tissue, or healing, is essential to normal body function. Without this, we would lose lung function with every infection we developed since childhood. Scar tissue may be a way to “cut the losses” and control inflammation when healing cannot be accomplished. Scar tissue in the lung is currently an irreversible process. However, that doesn’t mean that lung function cannot be improved. One can focus on relieving the airway spasm and constriction, decreasing the inflammation and mucus production, and improving the respiratory muscles and significantly improve these respiratory systems.

Can lung damage be prevented or reversed?

So where do you start? First, stop the damage. The lungs need to be protected to prevent further injury and scarring. Avoiding tobacco smoke and other pollutants is essential. You also need to control infections early, so they do not lead to a severe pneumonia that may leave significant damage and scar behind. Talk with your doctor about vaccinations. The influenza vaccination is offered every year, and the pneumonia vaccine is also offered as a one-time vaccination with a future booster. Vaccines are highly effective for these two very common and potentially deadly infections and I highly recommend them when possible for those with lung disease.

The second step is to control chronic inflammation from chronic irritants. It is hard to live in an irritant-free world. From pollution to chemical cleaners and other indoor and outdoor toxins, there is a lot that can irritate the lung. For patients with COPD, they may frequently be prescribed an inhaled steroid to control inflammation. This medication is something that must be taken daily to be effective. While it may help prevent future hospitalizations, people rarely notice a difference in their day-to-day symptoms. It is one of those important medications, which is good for prevention, but does not give any instant gratification; so, it is difficult to convince patients that they are getting benefits from it. Most steroid inhalers come with warnings about bone loss and steroid dependence. However, this is a topical medication which is breathed directly into the lung and really has minimal systemic or body-wide effects. The most common side effect usually seen is oral thrush, which is a fungal infection that comes when the mouth isn’t rinsed free of the medication after dosing. If you take your inhaled steroids right before you brush your teeth it helps to ensure that a good cleaning gets done.

What medications are used to make breathing easier?

The next weapons in the arsenal are the long-acting anticholinergics. The nervous system controls the spasm and constriction of both the large airways and the small airways. The cholinergic (or parasympathetic) branch of the nervous system controls the large airways, while the “beta” (or sympathetic) branch controls the small airways. The large airways are the ones which are the most effected in people with COPD and therefore constriction is best stopped by anticholinergics. These come in a short-acting (multiple doses per day) and long-acting (one daily dose) variety. Frequently, these give significant relied to patients with shortness of breath (“dyspnea”). Unlike the inhaled steroids, the relief is usually felt over a matter of days. It is not the quick happy sensation an asthmatic has when using an inhaler during attack, but the ability to do more without becoming “winded.” For example, walking from the bedroom to the bathroom or going up the stairs, without having to stop and catch your breath. The medications that affect the small airways are less effective for patients with COPD and are used more commonly in asthma.

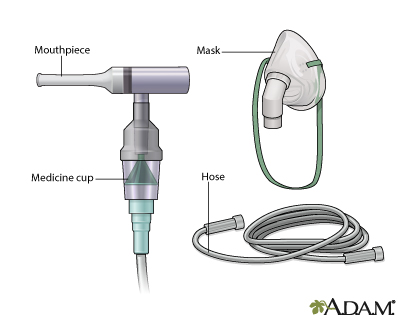

Does it matter if I use an inhaler or a nebulizer?

The most important thing to remember about respiratory medications, in general, is that if the delivery devices (inhalers, nebulizers) are not used properly, the medication will never get to the lung. It will end up absorbed by the mouth and stomach and will be useless. Be sure to review the correct use of all inhaled medications with your lung doctor. Bring the medication with you to the doctor’s office and have them watch you take a dose. Patients often say that the medication their doctor gave them didn’t help, only to find that they weren’t getting the medication because of incorrect use of the delivery device. Just because you squirt it in, does not mean you did it correctly. Also, many of the anticholinergics have bromide or peanut oil. If you are sensitive to these agents, discuss with your doctor before use.

Is there a pill to treat COPD?

There are also medications which are taken by mouth, and not breathed-in, which are used for COPD. I would just like to mention two classes. The first is one of the oldest medications used for COPD, and it is theophylline. This medication has multiple methods of action but does help to open the airways and improve shortness of breath. It must be closely followed for side-effects, which usually also requires frequent blood work. The second, is one of the newest medications for COPD, roflumilast. This medication is used for prevention of exacerbations and hospitalizations in patients with moderate shortness of breath and increased sputum. It does not require lab work but cannot be used in patients with liver disease.

Finally, there are other medications which are used to help to decrease mucus production, boost respiratory muscle function and improve blood flow to the lungs. These are used as a second-line treatment in COPD and will be explained as primary treatments in other sections of this book.

Are there any exercises that can be done to improve lung function?

As always, a well-balanced diet, maintaining a healthy weight, and exercise are all important. There are several exercises which can really improve breathing.

The first is pursed-lip breathing. With chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the big problem is obstruction. The narrowed and inflamed airways allow air to come into the lungs very easily, but do not let it out. If you ask someone with significant COPD to blow out the candles on a birthday cake, they just can’t do it as fast or as easily as a healthy person of their same age. The air gets trapped inside. When enough air is trapped inside, the lungs become over-expanded, like an overfilled balloon, and it is very hard to put any more air in. Most people complain that they “can’t get a deep breath in,” paradoxically, this is almost always because they “can’t get a deep breath out.” One quick test to see if this is a problem is to try and blow out as fast and hard as you can. If it is not that fast (i.e., the birthday candles are still lit), then you probably have some air trapping. While the anticholinergic dugs help to limit this constriction and trapping of air, there is also an easy maneuver that can be done. All you have to do is purse your lips (as if for a kiss, or after tasting something sour) and slowly exhale (very slow, for a good minute if you can until all the air is emptied out of the lungs). It also helps to sit forward with your hands on your knees. Repeat this for several breaths until you feel less winded. This is usually taught in a pulmonary rehab class (which is highly recommended), or at Yoga.

Another breathing maneuver worth practicing is a cough, which requires a deep breath in and forceful breath out. There is a plastic toy, which can help to train you in these maneuvers. It is called an incentive spirometer, otherwise known as “that little plastic thing with the ball that goes up and down which they gave me after my surgery.” The incentive spirometer is a plastic tube with a ball that lifts whenever you take a deep breath in and hold it.

Finally, leg exercises (more than arm exercises, breathing exercises, or heavy lifting), have been shown to improve respiratory muscle function. You should always choose to do an activity that you like, be it aqua aerobics, shopping mall- walking, or yoga. If you can talk in complete sentences, you are exercising appropriately. If you find that you cannot talk in a complete sentence, rest, and then begin the exercise again.

Is there anything that will reduce my risk of dying from COPD?

There are only a few things that decrease mortality from COPD. These include smoking cessation, vaccinations, and the use of continuous oxygen (24 hours a day, every day).

When will I need to be using oxygen?

If lung function continues to decline or other illnesses develop which increase the demands on the lung (heart failure, pneumonia, et cetera); then some of the functions that the lungs were previously able to perform on their own, may need the assistance of oxygen. The heart and the brain both need oxygen to function. If your brain is not getting enough oxygen, as determined by oxygen measurement from the blood, you will need supplemental oxygen all the time. If oxygen is only used part of the time, then the body will sense the lack of it, and try to compensate for the problem. Like many patients say, “You have to keep the hose in the nose to get the O’s [oxygen].”

You may have just gotten excited in hearing that the body tries to compensate, and while in the short term that is a necessary quick fix, in the long run it will lead to more damage. For instance, red blood cells carry oxygen to its destination. If the body feels it is not getting enough oxygen, it may make more red blood cells to try and increase oxygen uptake and delivery. The problem is that you have the current amount of red blood cells (and not a higher count) because blood is a liquid which must travel through a tube (vessels). The more red blood cells you put into the liquid the more clogged and clotted the tube can become over time. Clogged vessels obviously have difficulty doing the job. This may lead to the body making more blood vessels, which is also one of the steps linked to developing cancer and other health problems. The point is, if you need oxygen, you need to use it all the time to prevent abnormal body defenses from kicking in and making other systems in the body work harder or fail in order to perform this function.

When will I need to use an artificial respirator or mechanical ventilator?

Besides having the oxygen get in, you need to get the bad air or carbon dioxide out. Now in someone with severe obstruction and air trapping, which is not an easy task. Exhaling, or breathing out, is usually a passive sort of thing that requires minimal work or effort on the part of respiratory muscles. The more obstruction and air trapping there are, with narrow constricted airways to push through, the more the work of breathing goes up. Therefore, stronger expiratory respiratory muscles are needed. If the demand is more than the supplied muscles can handle, there is a need for another medical device known as a “ventilator.” Simply put, ventilators are devices that push air into the lungs for people who are not strong enough to pull it in on their own. There are two basic types. Ones that work with a mask on the face or nose (noninvasive ventilators, also known as CPAP or “BiPAP”) and the traditional mechanical ventilators or respirators which require a tube down the mouth and throat, or directly through the skin of the neck (tracheostomy). These machines perform the “work of breathing,” which the respiratory muscles cannot do. If one can remove this extra burden from the lungs (for example, by curing a pneumonia with antibiotics), then these ventilators can be used temporarily, and the patient will again be breathing on their own. If the extra workload cannot be reversed, for example, muscle paralysis from an accident or stroke), then the person may need to remain on a ventilator to remain alive.

Ventilators are tools, and thinking about whether you would want mechanical ventilation, may stir up a lot of emotion and confusion. This information is also contained in a living will or advanced directive. Many patients have elaborated advanced directives and other legal documents trying to cover every possible situation and outcome. These are often confusing and conflicting. Using simpler language to express their wishes to their physician and their family is usually a better initial approach. Thin about the following alternative scenarios. First, “I want to be on a ventilator to sustain my life, even if I become dependent on it and need to stay on it for the rest of my life.” Second, “I want to try a ventilator, but keep me asleep or unconscious as long as you can while I am on it. If it looks like I will be dependent on a ventilator for the rest of my life, then I want the ventilator stopped. Please keep me comfortable, as I do not want to suffer.” The third option, “Put me on a ventilator, then discuss with my spouse or children, they know what I want.” Finally, “I never want to be on a ventilator.” Similarly, the doctor should be able to give you a reasonable idea of your chances of coming off a ventilator. If you have a strong feeling about ventilators (to use or not to use), you should definitely tell your doctors and family, and make a living will. If your wishes are not known, you will automatically be put on a ventilator should you require one for survival. Also, if you are concerned about having limited functioning (ie, needing nursing home care), you may want to pursue different levels of advanced pulmonary care. Most patients who require mechanical ventilation will be transferred to a facility and usually will not return home.

Are there any surgical treatments for COPD?

There are multiple options for treatment of advanced COPD. Some have become more accepted, and some are still considered experimental. These include procedures to improve oxygenation: such as trans-tracheal oxygen (putting a small oxygen cannula directly in the lung via the skin or neck) and the more traditional tracheostomy. Some procedures are aimed at reducing air trapping and obstruction, such as, endobronchial valves and lung volume reduction. There are multiple medication trials. Finally, there is also the option of lung transplantation. A Pulmonologist is the best doctor to consult about advanced treatments for COPD.

What are the common tests my physician may do to evaluate my COPD?

Tests for monitoring COPD may include: pulmonary function testing, a chest x-ray, a CAT scan of the chest, pulse oximetry (noninvasive check of blood oxygen) arterial blood oxygen level, carbon monoxide level, alpha one antitrypsin screening, 6 minute walk test, echocardiogram or bronchoscopy.

Self-Check for Management of COPD

- I have a plan to quit smoking, and to avoid inhaling smoke, irritants, or pollutants into my lungs.

- I understand all my breathing medications and how to use them. I understand when to use my inhalers and when to use my nebulizer.

- I have my secretions or mucus under control and can keep my airways open and clean.

- I am maintaining a healthy weight.

- I am maintaining a regular exercise routine. I have done a course in pulmonary rehabilitation.

- I am updated on all my vaccines.

- I understand the different breathing exercises and have chosen to do the ones that I feel will benefit me the most.

- I have discussed future health care decisions with my family or friends. I have designated a family member or friend to be my decision maker if I am unable to do this. I have discussed with them my feelings at chronic ventilators, tracheostomy, feeding tubes and nursing home care.

- I have notified my doctor what my wishes are about experimental or surgical options for treatment.

Managing Doctors

- Primary Care

- Pulmonary

- Ears, Nose, Throat (ENT)

- Surgery

Links